.

.. .

.

.Two Republic of China Kuang Hua-6 fast attack missile boats sail in formation during a combat readiness exercise at the Zuoying Naval Base in Kaohsiung,

.有美國智庫發布文章指出,為了應對中國可能帶來的威脅,美國近期不斷加速集結在第一、第二島鏈部署的軍事力量,並為可能在 2026 年爆發的台海衝突做更進一步的準備。

.美國保守派智庫「哈德遜研究所」( Hudson Institute ) 副所長邁克.沃森 ( Mike Watson ) 近期發表名為「為 2026 年台海戰爭做準備」的文章,認為中國可能在 2026 年發動台海戰爭,強調美國目前正在應對可能發生的衝突,集結來自第一、第二島鏈的各種軍事力量。.

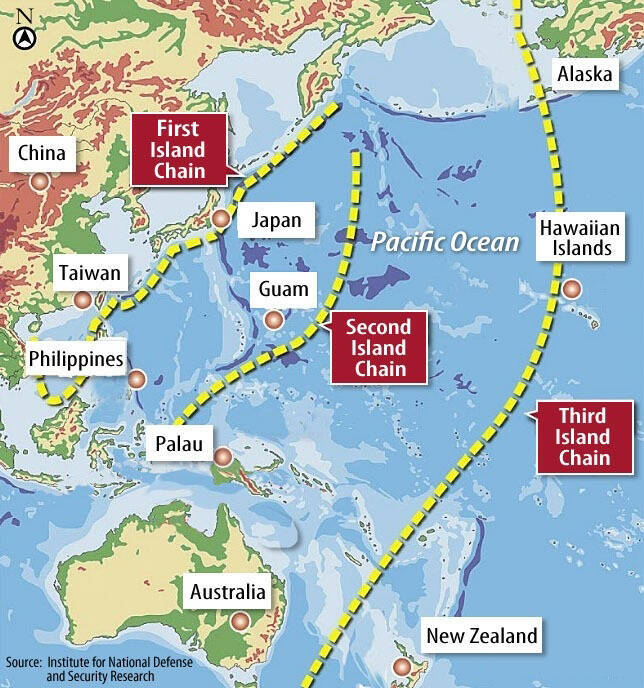

美國透過以日本、台灣、菲律賓形成的第一島鏈以及關島為核心的第二島鏈,持續限制著中國對外擴張的機會,近期更加強上述地區的軍備規模,試圖進一步遏制中國的野心。針對中國的「反介入/區域拒止」策略,美軍則以「分布式作戰」進行應對,試圖透過分散部署兵力與武器的方式,降低被解放軍同時打擊的風險。

與冷戰時期的防禦性措施相比,近年來美國逐漸強化印太地區的軍事部署,「很可能是為了即將到來的全面衝突,進行事前準備」。「地球村的故事」推測,美國可能仿照俄烏戰爭的「代理人戰爭」模式,透過支持台灣、日本、澳洲等國家,在避免自身直接介入的同時,削弱中國的軍事與經濟實力。

「地球村的故事」也強調,雖然美軍目前尚未在第一、第二島鏈地區出現大規模集結,但其在上述地區的軍事部署,已經足以對中國施加巨大的壓力。「地球村的故事」稱,雖然目前中國在軍事實力以及軍費開支等層面仍落後於美國,但解放軍也在爭對台海戰爭進行準備,甚至計畫強化兩棲作戰能力,並進一步推動海軍艦隊的現代化。

. .

.

.

.

.

國際戰略學者專家分析認為,美國已經無法抵抗中國,對於太平洋第一島鏈的防禦圈,因此許多美國智庫普遍性認為,海峽兩岸的戰爭會提前爆發? 2026. 開戰?

The US Marine Corps (USMC) has introduced new anti-drone systems to bolster air defense in the Pacific island chain amid growing Chinese military influence in the region, .

.

.While the Republican and Democratic parties plunge into painful realignments, China is making its own moves internationally. Taiwan has become a major flashpoint of the U.S.-China rivalry, and two books on the topic reveal not only some of the key arguments taking place in the United States about Taiwan, but also why this realignment is happening.

In recent decades, much of the professoriate has lowered its sights from the serious study of big issues to gaze fixedly at navels. This, as much as China’s generous treatment of its friends, explains how much of the credentialed class missed the implications of a rising, hostile Communist superpower. Tufts University’s Sulmaan Wasif Khan is still grappling with the big issues though, and he tries to get to the heart of the Taiwan problem in his newest book. The Struggle for Taiwan is well written and forcefully argued, but it contains many of the flaws that plague his profession.

As Khan sees it, "confusion has played the starring role" in the unfolding saga of China, Taiwan, and the United States. "Luck, more than deterrence, prevented a conflict" in past confrontations between China and the United States in the Strait, so deterrence is a thin reed on which to rest a country’s existence. As he sees it, getting back to a good relationship with China, or, failing that, a neutral one, is vital for the United States’ well-being.

He is right that the Taiwan question is perplexing, since it has given Americans fits for decades. In 1949, George Kennan thought he had discovered the perfect way to cut the Gordian knot: Invade Taiwan, forcibly displace Chiang Kai Shek and his 300,000 troops, then make Taiwan independent. Kennan submitted a memo about it and, after briefly reconsidering the matter, withdrew it the same day. Curiously, Khan describes this madcap scheme as "a profound reading of the situation." He is correct that "if Washington was serious about independence, this was precisely the form of policy that was required," which is why no one in Washington contemplated it for long. There was no appetite for anything as self-defeating as a "Theodore Roosevelt-style assault" on Taiwan.

As Khan tells it, Chiang was an untrustworthy ally who maintained his grip on power through the connivance of the "China lobby," which was largely motivated by McCarthyism and greed for Chiang’s lavish gifts. Mao, however, "wanted a rapprochement with the United States," which he demonstrated when he "carefully calibrated" his repeated shelling of Taiwanese-held islands and sparking crises with the United States. After Nixon visited China, Taiwan was an irritant in the Sino-American relationship, its democratization almost as much of a headache as the old dictatorship.

Readers who are familiar with the long sweep of U.S. foreign policy may scratch their heads at this book. Chiang was often prickly, but he was not nearly as difficult as other allies like Charles de Gaulle, so it can be hard to see what all the fuss is about. Khan later depicts a recent controversy in Taiwan about importing American pork as an example of the United States running roughshod over other countries. But nearly every country on earth is asked to take American farm products: Just ask the French about American chickens. Khan suggests Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 visit to Taiwan with her son in tow made the Taiwanese wonder if the price of support was greasing American palms. But considering his sources are a Chinese propaganda website and a story about congressional Republicans criticizing Pelosi fils’s China ties, it is not clear if any Taiwanese agree with him.

Khan’s analysis of the forces driving the confrontation over Taiwan leaves him trapped in an intellectual cul-de-sac. For example, he argues that if the United States had responded more forcefully to Chinese provocations in 1958 and 1995-1996, and if China then raised the ante in a destructive way, a war might have broken out, so deterrence is unreliable. Conversely, he says, "U.S.-China relations have worked best when the two sides have maintained a commitment to keep talking to one another." But China cuts off communications during perilous moments to increase the pressure on Washington, so his statement amounts to "when there are no problems, the relationship is better." And since his counterfactuals did not actually happen, they are not evidence of deterrence failure.

His way out? Perhaps China could simply allow Taiwan to declare independence, or the United States could offer enough incentives that China would agree to renounce the use of force for a time. China has never agreed to that though, so Khan’s fallback is to threaten sanctions but eschew military force. This did not deter Vladimir Putin from invading Ukraine though, so his plan seems guaranteed to start a war.

As the university has lost its moorings, think tanks have filled the gap to provide government officials with serious outside analysis and recommendations. Matt Pottinger, a deputy national security adviser for Donald Trump and one of the Republican Party’s top China hands, assembled a team that includes many of his Hoover Institution colleagues to study the Taiwan problem. In their book The Boiling Moat, Pottinger, et al, argue that the China problem is a difficult one, but that the United States can maintain peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. The key is deterrence.

Pottinger and his coauthors point out that the Taiwan issue has grown more perilous not only because of China’s massive military buildup, but also because Xi Jinping has indicated that he is willing to use this military. Unlike his predecessors, Xi has warned American officials that he might invade Taiwan even if the island democracy does not declare independence, and he has told the Chinese Communist Party and its military to prepare for war. As Pottinger, et al, see it, keeping Taiwan free will be difficult, but not impossible. They offer "practical and feasible steps that democracies should pursue urgently to deter Xi from triggering a catastrophic war over Taiwan."

A Chinese invasion is the most spectacular threat to Taiwan’s independence, even though it is arguably not the most probable, and the authors show how to defend against it. They prefer "deterrence by denial—getting the adversary to understand that its military strategies have little chance of success, thus discouraging it from aggression." The Chinese military’s center of gravity would be the naval forces needed to ferry the Peoples Liberation Army onto Taiwan, so the authors describe how Taiwanese defenders can bloody the invaders while American satellites and surveillance tools identify targets for prowling submarines and bombers to swoop in. The United States is not making enough of these bombers, submarines, and weapons to pull this off, but increasing production rates by 50 percent would only cost about $7.5 billion. Unlike other advocates of "deterrence by denial" for Taiwan, the Hoover team sees no reason to cut off arms to Ukraine, which needs very few of the kinds of weapons useful in a Pacific war.

Because an invasion would be daunting, China might prefer other options, such as blockades and propaganda campaigns, and The Boiling Moat contributors look at how to thwart those plans too. Many of these can be defeated through relatively simple methods, such as stockpiling enough food and fuel to outlast a blockade. Nearly all of them involve United States, Taiwanese, and other friendly militaries collaborating much more closely, both during the planning stage and if war breaks out.

Khan suggests the current tensions with China are largely due to red-baiting Americans, but the international team Pottinger assembled belies that claim. Australian, Danish, Israeli, Japanese, and Taiwanese former officials and policy experts contribute short, brisk chapters about how to convince China to give peace a chance.

The Boiling Moat is full of sensible ideas to reduce the risk of defeat, and therefore of war, but the major question is how receptive policymakers are to it. Donald Trump said in a recent interview, "You know, we’re no different than an insurance company. Taiwan doesn’t give us anything." Joe Biden has said repeatedly he would defend Taiwan, but his conduct toward Ukraine does not inspire confidence. And no one knows what a future leader of either party will think.

Like many policy books, The Boiling Moat is not meant to be a beach read. The prose is generally quite good, but much of the book covers missile production rates and force planning requirements that will appeal more to practitioners than the public. But as American politics takes a more populist turn, Pottinger and his fellow authors are showing the credentialed class how to revitalize their professions. They are soberly assessing some of the biggest issues facing the country and developing options to keep the American people, their friends, and their allies free..

..

限會員,要發表迴響,請先登入